* economically speaking

Two events from recent history:

- The Berlin Wall fell in 1989 – the symbolic end to communism as a way of organising society and the economy.

- With the collapse of Lehman Brothers and government rescue of failing banks, Free Market Fundamentalism – my term for neoliberalism or neoconservatism – collapsed in 2008.

No serious commentator in the west or in the former Soviet bloc doubts event one, but many are still in denial about event two. Gideon George Osborne is one such person.

The “EffEmEffs”

Now, to back-track a bit. (This is not meant to be a lecture on the history of economics. Much, perhaps too much, has already been written on the clash of the ideas of Keynes and those of Hayek and Friedman. Suffice it to stay, the latter got the upper hand nearly forty years ago and won’t let go.)

As is well known, the core message of free market fundamentalism is that market forces are the best and most efficient way of organising society and the economy. Each individual pursuing his or her own interests leads to the best possible outcomes. Governments should “keep out” from interfering in the workings of markets.

I was instinctively against such ideas when they first emerged into public debate in the early 1980s, but could not articulate a full, coherent argument against the FMF movement.

Markets Increase Inequality

It was clear even then that free markets, left to themselves, would, over time, lead to ever increasing levels of inequality. The “invisible hand” of millions of individual decisions about which products and services would be bought and sold, and at what price, inevitably leads to an economy at odds with people’s preferred wishes overall. There would be more luxury goods in the world and fewer doctors, nurses and teachers than people would choose if asked to express their priorities directly. The reason is simple: in free markets, choices are made by the “votes” of each transaction: the more money someone has, the more “votes”. Markets thus respond in a way that makes poor people poorer and the rich richer. Even the smallest initial levels of inequality, processed through the amplifying effect of repeated transactions with the rich getting most say, lead to an ever-widening gap between rich and poor. This is an immutable law of free markets.

The Psychopathic Economy

Imagine for a moment, if you will, that the economy is a person. We would say that that person, exhibiting the behaviour required by the FMFs, has a severe personality disorder. Such a person would have a high risk of antisocial, predatory or even criminal behaviour. In lay terms, we’d call them a psychopath.

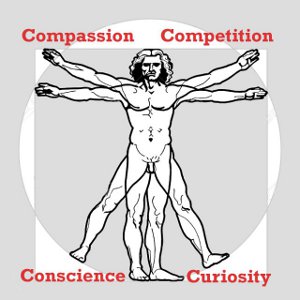

Now, using the Four Cs framework from my earlier post Being Human II: The Four Cs, it is easy to see why this should be so. Free market rules (i.e. pursuing self-interest) do not represent human thinking. The twin attributes “curiosity” and “competition” are modelled fully in the workings of markets. But the balancing attributes of “conscience” and “compassion” are missing completely.

Now, using the Four Cs framework from my earlier post Being Human II: The Four Cs, it is easy to see why this should be so. Free market rules (i.e. pursuing self-interest) do not represent human thinking. The twin attributes “curiosity” and “competition” are modelled fully in the workings of markets. But the balancing attributes of “conscience” and “compassion” are missing completely.

George Osborne is our national cheerleader for the “EffEmEffs”. And it’s in that way that he is only half human.