When I read a report of someone who’s died and see the phrase “battle with cancer”, I know the copywriter’s brain was on auto-pilot. Quite often the word “brave” appears before the word “battle”. (We all love lots of allusive alliteration!)

My first wife died of cancer at the age of 48. From my second hand perspective, neither “brave” nor “battle” gets it right. When diagnosed with terminal illness, after the initial shock, it’s only natural to try to spend your remaining days as fully and as joyfully as your health allows. Anything less would be a senseless waste of precious days. That’s not brave, that’s common sense. Moreover, cancer is an illness. It doesn’t convey any moral value on someone who lives longer than someone who dies sooner. “Battle” implies winners and losers – and heroes and cowards. Let people and their loved ones live their lives without some judgmental value being placed on their manner of living – or dying.

“Battle” – and “hero” – are much abused – and overused – words.

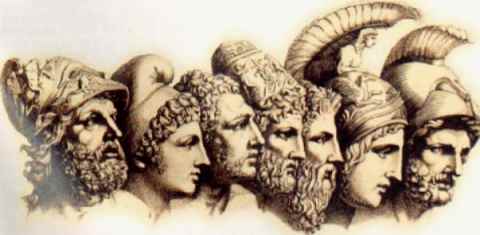

Homeric Heroes

The ancient Greeks loved a good hero. Here’s a list of quite a few to choose from. Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and Odyssey, tell morally uplifting tales of heroes and heroism, of wars and battles. They set a kind of model paradigm, an ideal against which to judge all people. During the 18th century enlightenment period, these classical themes were revived, in part as an antidote to the stifling religious conformism of the mediaeval period. These cultural influences survive in some form to this day.

Chivalric Knights

In mediaeval times, knights operated a code of chivalry as a guide to a good, heroic life. Some of the rules of this code reflect mediaeval thought: fear of God and a duty to serve your (earthly) lord, for example. But others still have a modern moral resonance. “Fight for the welfare of all” and “protect the weak and defenceless” have modern equivalents. Some notions that were popular a generation ago but now seeming slightly old fashioned, such as men not swearing in front of women, can be traced back to the chivalric code. But physical, as opposed to verbal, battles were all the rage at the time of the knights. Heroes, too, were judged in military terms.

Our Finest Hour

Britain clings nostalgically to “our finest hour” during World War II and the Battle of Britain in particular. It is viewed as a time when there was a sense of common purpose and the pain and suffering of war was shared by everyone, not just an elite band of knight warriors. It would be fair to say there were countless examples of heroic acts performed by both military and civilian populations during this period. In a real sense, we were all in it together. The battleground of the Battle of Britain threatened every part of the land.

Battles Physical and Metaphorical

Fortunately for us today, battles are generally verbal or metaphorical: few of us experience a real physical one. And its honourable counterpart, heroism, can take many forms. The stranger who risks his or her life rescuing a drowning child. A neighbour pulling someone from a burning house. Emily Hobhouse and others, who campaigned vigorously for a peaceful end to the First World War in the teeth of public opinion. Unarmed police officers risking their lives tackling armed criminals. The many different people from all walks of life honoured annually in the Daily Mirror’s Pride of Britain Awards. And of course the many campaigners fighting the British establishment for 27 years to get truth and justice for the Hillsborough 96.

So it will come as no surprise that I object to the British Legion’s choice of name for their fundraising campaign. It attempts to equate the word “hero” with service in the UK armed forces. There is nothing inherently heroic in agreeing unconditionally to fight for one’s country. This is especially so when I believe that hardly any British military action since 1945 has any moral or ethical basis. Most of it has solved nothing or made matters worse in the medium to longer term. The Legion’s branding is pure propaganda.

Battles and Heroes

So, what do I conclude? We should be grateful that most battles today are not of the military kind. It’s a positive sign of the progress of what we call “civilisation”. Heroism takes many forms, most of it far from a battlefield. And cancer is a disease, not a battle.