I’ve been a school governor for over three decades. Here are some ideas which help to explain why I do it.

1970s: The Germ of an Idea

In the early 1970s, I was flat sharing in London. One of my co-tenants was an Australian woman who normally worked as a teacher. At the time I knew her, she was on an extended working holiday in the UK. In a conversation with her, she made a number of assertions.

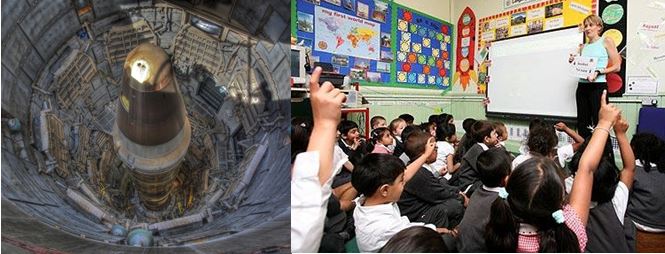

The first was about the relative benefit to national economies of education and military spending. The second was on their relative moral worth.

Economic and Moral Benefits

The economic arguments are worth repeating, in particular the multiplier effects of spending in these two areas. Every pound (or Australian dollar) spent on education is repaid many times over by the enhancements in the skills – and value to the economy – of each generation. In turn, these skills could be passed on to succeeding generations in a form of virtuous circle of benefit. Military expenditure, by contrast, is used for killing and destroying people and things (buildings, etc.) or, like nuclear weapons, are kept in concrete bunkers, do nothing for the whole period they exist and cost money to guard. Nearly fifty years later, these arguments seem a bit simplistic but still hold a basic truth.

But it’s the moral comparison which I still find most compelling. The moral worth to society of spending one’s career as a teacher seems the greatest of any as it is one person’s contribution to the skills and moral values of future generations. By skills I mean basic life skills such as patience, sharing, taking your turn (for the youngest pupils) through to more obvious basic “academic” skills such as reading, writing and numeracy through to a life-long passion for education: learning to learn. Moral worth comes from teaching respect, openness to others’ ideas and views, courage, perseverance, self-respect, tolerance and by school staff modelling these behaviours as they work.

Keeping the Peace 1

One way of “keeping the peace”, at least in the short term, comes through policing people’s behaviour and, in extremis, by military means. Such methods tend to rely on fear as a motivator: a poor one in my view. Fear, like some addictive drugs, is usually required to be applied in increasing “doses” to continue to effect. The law of diminishing returns applies here. Fear can also, of course, lead to resentment by the fearful.

I’m not denying – and I salute – those individual acts of courage which are unique to military service: putting oneself in the “line of fire”, so to speak. But I have very strong doubts about the moral and ethical basis of choosing a military career. My discomfort flows from the unquestioning obedience to orders from a “higher” authority. This is tantamount to signing a blank cheque for any military-related government policy decision, no matter how morally dubious. Please don’t misunderstand: I’m not a pacifist: some degree of “defence” expenditure is necessary. But I would struggle to find a morally defensible casus belli since World War Two.

Keeping the Peace 2

I digress, so let’s get back to education. The school where I am Chair of Governors is situated in the most multinational, multi-ethnic part of a town which is itself quite multicultural. Broadly speaking, it’s a relatively peaceful place and people of many nationalities and cultures generally get along fine with each other. We have around 45 different nationalities represented in our school, a fact which we celebrate. Mutual respect is hard-wired into our values. A neighbouring school on the same “campus” site shares our values.

As I said recently to the Chief Education Officer in our Local Authority, I firmly believe that the values we encourage in our pupils contribute strongly to the community coherence of our town.

British Values?

Which is why, unsurprisingly, I get annoyed when politicians (or Ofsted aping the words) bang on about “British” values. For the record, to the best of my recollection, it was Gordon Brown who, as Prime Minister, started it. The Tories have continued to emphasise this concept as part of the English nationalism and exceptionalism which has, tragically, taken over the Party. To the idea of “British” values, I simply say this: there is no such thing. The values we emphasise in our school are to be found in any liberal democracy in, let’s say, Northern Europe at least. Similar values can be found, to a greater or lesser extent, throughout “Western” liberal democracies.

I would like to say that they are “human” values, but, sadly, I don’t see that they extend that far.

Measuring the Wrong Things

The reality is that we live in a country where Ofsted has been given the job to assess and judge schools and similar institutions. My recent post Abolish Ofsted? goes into more detail on this. The inspection framework doesn’t measure those valuable cultural and societal issues mentioned above. There are some practical reasons for this. “Community coherence” is hard to measure: it is quite subjective and the effects of “good” education in this dimension may take decades to show. Today’s Guardian opinion piece on the importance of creativity in our education system is another example.

A good Ofsted inspector will understand this and (a) make an effort to understand the context of the school and (b) take a holistic approach which makes due allowance for the softer, harder-to-measure aspects of a school’s performance. It is a pity that many Ofsted inspectors are not up to the job in this respect.

Respect

So, my deepest respect goes out to teachers: it’s a hard but rewarding job educating our future citizens. And I salute their “critical friends”, my fellow School Governors, volunteers all (as far as I am aware). In these troubling times, our very future as a civilised nation depends on their dedication.