About 15 years ago, a group of Head Teachers, together with the Chief Executive of our group and I, went on a fact-finding and exchange of ideas to a group of schools in Doncaster. We travelled by train and the consensus route involved a change at Derby. The outward journey passed off uneventfully and we completed our business. The first leg was by Virgin Cross Country and the second by whatever name the operator of the Midland Main Line had at the time: it’s changed hands so often I forget.

We had 12 minutes “transfer” time at Derby station and we knew it was a simple cross-platform transfer: about a 30-second walk. A succession of minor holdups meant it looked like we would arrive in Derby 12 minutes late. No one was particularly bothered, as we knew how easy a transfer it was.

We arrived at Derby only to see our train pull out of the platform. It was dusk and my most vivid visual image was of our train’s red tail lights disappearing into the distance. As the Chair of the group, I understood the need to act professionally and chose my words very carefully, so there would be no misunderstanding. I approached the young man who had obviously flagged off the train we wanted. I said “Will you please tell me who has the authority on this station to hold that connection?” His reply surprised me at the time: “Nobody”, he said. There was no point in extending the conversation, so we all went into a huddle and waited for the next London-bound train.

Here’s a picture of a train like the one we missed. (This picture was taken at St Pancras in 2005). I tried to get the right livery – for rail buffs. They, and anyone who’s actually travelled by train more than 20 years ago will note that the rolling stock still betrays its BR origins. They’d only painted the loco. And to anyone north of a line from the Trent to the Mersey, you’d be bloody lucky to find any train that isn’t old hand-me-down BR stock covered in several layers of different coloured paint – unless you’re lucky enough to hop on a passing train on the way to or from London. Northern Powerhouse? Don’t make me laugh.

A Trip to Brussels

At about the same time, I went to visit an old university friend who was now working there. He joined British Rail a few years after graduating. His dad was a railwayman: like the military, working “on the railways” seemed to be in the blood. We had a couple of bottles each of Belgian beer: I knew already how tasty it was, but I hadn’t observed just how strong (7% ABV)! We both got a bit pissed.

He told me, when the railways were privatised, he was moved over to Railtrack – of which more below. As, by then, he was a fairly senior BR manager, he was put in charge of a project. This was to design a system of incentives to deal with what happens when trains are delayed that would fit with the new, fragmented structure. Its basic design was this:

- A train is late.

- Someone must be to blame.

- Find out who: this pitched Railtrack against Operating Companies, Operating Company against Operating Company.

- Settle any disputes: this was bound to take up a lot of time and resource.

- Debit the faulty party and credit the other party.

At the end of the month, add up all the debits and credits for each company (they’re all profit-maximising private companies, so there are bound to be more disputes at this stage. Settle the accounts (details unknown).

My immediate thought at the time was “gravy train for lawyers and accountants” (no pun intended – then!) but said no more.

The thought struck me in the last day or two: do you know what we have here? It’s an algorithm! Not of the lines of computer code sort, like Facebook and Amazon, but in the rules of the game. And the game, if you’re a profit-maximising entity, is to end the month in net credit. So you instruct your staff on how they must behave to maximise your company’s profits.

Compare this to a similar experience I recall from my student days. Birmingham to Oxford on a Sunday, change at Banbury. Owing to the dreaded “weekend engineering works (probably – I can’t remember) our arrival at Banbury was a few minutes late, after the scheduled departure time of the connecting service. Some relatively junior member of the station staff would have said something like “hurry along” and we all scuttled across the platform. The result? Everyone on both trains was a couple of minutes late – no big deal.

Who Benefits?

Well, the lawyers, accountants and shareholders, obviously.

So who else? The staff? Compare or man in Banbury with the one in Derby – yes, they were both men. The Derby man looked younger than my memory tells me about his Banbury counterpart. But, there again, police officers all look about 12 now, so maybe it’s just me. Think about it. The guy in Banbury was probably proud of working “on the railways”, just like my friend and his dad. His day would have been boosted, just a tiny bit, because he had used his common sense and held the connection so that everyone got to their destinations on time – or near enough. The important point is that he had the authority to do so. Nobody gave it much thought, it might not even have been written down in some rulebook, but everybody knew that’s how British Rail worked.

Now think of the young man at Derby: he probably felt slightly embarrassed about the answer he had to give me. The key point is that he had been disempowered and deskilled. He was reduced to being just a pawn in someone else’s game. A unit of labour. Wave the flag. Follow the rules. Which of these would have the higher self-esteem after years of doing each of the two jobs? It’s not hard to draw the obvious conclusion.

So, anybody else? Not the Passengers, obviously: half the people (or at least those So let’s add paint suppliers to the list of beneficiaries.

I already know that 80% of us support Labour’s policy to renationalise the railways. And that’s mainly beacuse (a) they’re very expensive, with walk-up fares and deason tickets costin up to 3 times those in other parts of Europe. And they need about 3 times as much public money to prop up unprofitable bits and pay for major capital projects.

A Word About Words

I absolutely, unequivocally refuse to use the “C” word when describing rail passengers. Customers buy baked beans: it’s a transaction. Rail travel is a whole different experience. Just ask Michael Portillo or his millions of regular viewers – that probably includes you! The people who travel by train are Passengers. Capital P. Using the C word reduces rail travel to a commodity. That’s another part of the problem.

Railtrack

So, finally, as promised, let’s turn to Railtrack: the company that liked to kill its users. I’ll explain.

Formed in 1994 to take over the infrastructure assets of British Rail, it was floated on the Stock Exchange 2 years later, a few people in the know mainly city types and rich friends of Government, made a killing with the shares. This always happens with privatisations and represents a one-off transfer of wealth to a privileged few (let’s call them the elite shareholders). Public and freight users of the railways began to express gave concerns about Railtrack’s safety and improvement record. The regulator, John Swift, appointed earlier by the Tories, continued to treat them with a soft touch.

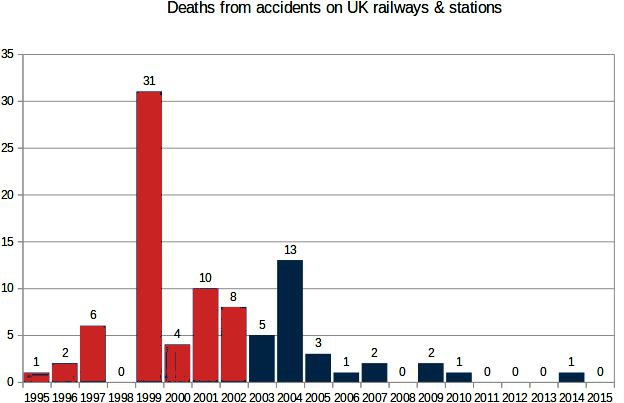

Following a Labour election victory and the Southall crash (1997, 6 dead), John Prescott (in his role as transport secretary) took a much tougher line and appointed a much tougher regulator, Tom Winsor. The crashes kept coming: Ladbroke Grove (1999, 31 dead), Hatfield (2000, 4 dead) and Potters Bar (2002, 7 dead) As well as the 50 dead, a total of at least 769 people were injured.

So what had been happening inside the company? The clue is in the expertise built up by the staff over the years: remember the pride and father and son working on the railways examples above? Let’s face it, much of BR’s expertise never got written down. Experienced staff tended also to be more expensive. Finding themselves in an alien profit-maximising environment, I guess some just left. But Railtrack had 3 choices: (a) wait until the individual retires at normal age; (b) offer early retirement / “voluntary” redundancy; (c) offload to subcontractor. Given the cultural liking for sub-contracting to cut costs and save money, each subcontractor had the same 3 choices, including offloading to their sub-subcontractors. The important point to note is that expertise was either lost altogether or fragmented over a myriad of subcontractors and nobody knew where the “experts”, or certainly Railtrack didn’t, in any systematic way – always useful in times of emergency, e. g. just after a big crash.

In other words, Great Britain, pioneer of rail travel in the 1820s, had wantonly lost the ability to run a safe and reliable railway service!

Data for this graphic and the numbers quoted come from this Wikipedia page: the Railtrack years are easy to spot, even without my colouring! Most of the narrative is adapted from here.

Railtrack panicked after Hatfield; the susbsequent repairs across the network cost £580m. I can do no better than quote Wikipedia verbatim here: “Because most of the engineering skill of British Rail had been sold off into the maintenance and renewal companies, Railtrack had no idea how many Hatfields were waiting to happen, nor did they have any way of assessing the consequence of the speed restrictions they were ordering – restrictions that brought the railway network to all but a standstill”. Yes – I was one of millions caught up in that time, a journey to London on a “fast” train, normally taking 40 minutes, took 2 hours 15 minutes: I found it excruciating: every time we got anywhere near a point of danger (typically, literally, points!), the train slowed to 20mph before speeding up to the next one. I cannot imagine what it was like for commuters at that time.

Public revulsion and a share price hit did it for Railtrack (the repair costs and a massive overrun on the WCML modernisation were the main causes of “exceptional” losses.

Shareholders’ Reaeguard Action

The Government decided to renationalise Railtrack and form Network Rail. There was one last sting in the tail, the elite shareholders staged a revolt and staged a very effective and time consuming legal fight to hang on their ill-gotten gains – or to have their cake and eat it, as we say today. This consumed an awful lot of Ministerial and civil service time and energy which could have been concentrated on setting up a safe and reliable railway in public hands. So there are people out who see their own selfish financial interests rather than people’s i.e. rail Passengers’ lives. So I dedicate this blog post not to tem, but to the 42 “hypothetical” people who, statistically speaking, died during Railtrack’s dismal 8 year stint at running the railway. [Calculation: Railtrack deaths 62 over 8 years (average 7.75), Network Rail 28 over 11 years (average 2.5); excess (7.75-2.5)*8 =42.]

And , above all I dedicate this to the memory of the 50 real dead, their friends, relatives and loved ones, who lost their lives at Southall, Ladbroke Grove, Hatfield and Potters Bar.