Normally, I’m not one for over-simplification. When I see TV and radio* programmes, journalists and politicians reducing a discussion to simplistic, black-and-white terms, I want to cry out: “But it’s not as simple as that….!”

Today, I’m going to break that rule completely and boil down the answer to the question:

“What does it really mean to be human?”

to some very basic concepts – three, in fact.

Let me first put this into some kind of context. Roughly speaking, human beings, our species homo sapiens, have been around for 200,000 years, with proto-humans for roughly 2 million. Over that time, we have spread from Africa over the whole planet (if you count the base station at the South Pole). And in that time, we have clearly become the “top” species in terms of our impact on life on Earth.

What is it that makes us so special? Well, clearly the development of language and “higher order” reasoning are often mentioned. Also, it’s often said that we are the only species to be aware of our mortality, but how we can know this I’m not sure!

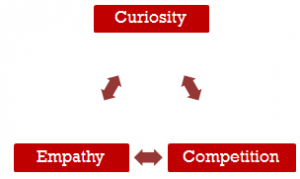

This is all very well, but what, at its most basic, do we mean when we say someone “is only human”? Think of it in terms of a simple triangular diagram:  Let’s explore each of these in turn.

Let’s explore each of these in turn.

Curiosity

Curiosity, or inquisitiveness, seems the most obvious human characteristic, so much so that it hardly needs explaining. Think of the look of wonder in a small baby’s eyes at it looks at a brightly coloured toy or rattle. Or, perhaps, think of the constant stream of questions from a back-seat four year old when you’re trying to navigate heavy traffic in a strange town!

All too often as we get older, that sense of joy and wonder in discovering new things seems to fade away. Some of us slide slowly into a safe world of fixed views and prejudices, with our ideas confirmed by a narrow group of friends and an equally narrow range of other sources of information. And yet, others manage to keep that child-like sense of questioning and searching for something new, right up to the day they die.

To me, curiosity is a kind of “umbrella” characteristic which informs and energizes the other two (which is why I put it at the top of the triangle).

Competition

Moving clockwise, we come to competition, perhaps better described as our competitive spirit. It’s the drive that makes us want to be winners, to make life better for ourselves and our loved ones. From our hunter-gatherer ancestors, competitiveness is associated with masculinity, and echoes of the role division between men and women from our earlier times persist today. Competition is much loved by politicians on the right.

For me, without competition, human beings, fewer in number, would still be contentedly eating nuts and berries in East Africa and what we call civilization would never have developed.

Empathy

Last, and by no means least, we come to empathy: the ability to imagine something from another person’s point of view. It’s the more compassionate, nurturing side of humanity, leading to ideas of fair play, altruism and group solidarity. Again, from primitive times, we tend to see empathy as feminine, not least because of the child-rearing role of women in traditional societies. Empathy and its derivatives tend to be the concern of politicians of the left.

Without empathy, I believe, we simply wouldn’t be here to discuss this – sometime over the past quarter of a million years, our unrestrained, aggressive selves would have wiped us off the face of the planet!

So there you have it: humanity summed up in just three words. I plan to use this framework to discuss some future topics: watch this space!

* Yes, I know you can’t see a radio programme!

SQUARING THE TRIANGLE

Interesting thoughts here! One at a time:

Curiosity: Agreed! I have a schools talk where I identify, as well as my Humanist ‘Seven Deadly Sins’, my ‘Seven Core Virtues.’ Curiosity is well up there. It has driven everything we like to identify as ‘progress’. What is distinctive about humanist ‘curiosity’ is that it is unrestrained, whereas where religions tolerate it, they insist that it be constrained within doctrinal boundaries.

Competition: As a classicist, I have no difficult recognising this as a virtue. It is the mainspring of the ‘heroic ideal’ of the Greeks’ foundational epic, the Iliad – ‘Strive to be the best.’ Attempts to suppress it, for example in the dreams of dewy-eyed romantics like Marx and Engels, simply make it break out in other ways. But in keeping with that other Greek precept inscribed at Delphi, ‘Nothing to excess’ (and unlike curiosity), it needs harnessing.

Empathy: I’m never quite comfortable with this as a virtue in its own right. What it literally means is the ability to read and predict others’ emotional responses to situations. A widely held theory of our ‘sense of self’ posits the existence of mirror neurons, to perform exactly this function, which is very useful in social species, such as most primates. Once we have learnt to perform this trick on others – creating in our minds a virtual counterpart of another individual – we can even do it to ourselves. Hence the self. The problem is that one personality type which tends to have this ability to a very high order is the psychopath, who uses it to his own advantage and to the detriment of others. Malignant demagogues know exactly what effect their words are having, and how to tune them to greatest effect.

So empathy, I would argue, is morally neutral. What makes it a virtue is when it is coupled with ….

Compassion.

So three C’s so far! Let’s go one further.

Other species are curious – we know what happened to the cat.

Other species compete. As Malthus and Darwin realised, this lies at the very base of our biological inheritance.

Other primates, and perhaps other intelligent social species, such as dolphins and elephants, show empathy, and not uncommonly compassion as well.

The really distinctive human attribute, in my view, and one that to humanists is (if the term is not too loaded) cardinal is …. drumroll….

Conscience

Conscience is Janus-like, in that it looks both ways. It reflects on past conduct and evaluates it. And it carries these reflections and evaluations forward as an element in directing future conduct. Other species ‘learn from experience’ – life would otherwise be pretty dangerous, not to mention brief – but we are, as far as we know, the only species that evaluates conduct, past and future, through a prism of morality, a sense of right and wrong. This faculty is, in its developed form, probably a function of symbolic language, with its ability to generalise individual experiences to abstract principles, and is therefore surely unique to our species and our immediate antecedents.

However conscience works, it has acquired in Europe, since the Enlightenment returned Greek philosophy to respectability, a status as the central plank of moral behaviour. For Humanists, this is especially true, because Humanism acknowledges no other moral authority. Religions do not see things the same way. The ‘Catholic conscience’ is shorthand for adherence to dogma – episodes such as the notorious petition opposing same-sex marriage that was circulated among its students by our local Catholic upper school. Islam insists that scriptural and scholarly authority always take precedence over individual conscience, and any who challenge this perspective, such as Quilliam’s Maajid Nawaz, are condemned by the orthodox mainstream as heretics and apostates.

So there are our four C’s mustered. True, a quadrilateral has less structural rigidity than a triangle. But perhaps that’s a good thing.

I’m much taken by your arguments and I’m likely to revise my ideas soon. I’ve also had an email feedback from a friend suggesting some reading material on the matter!