When did you last hear the Defence Secretary criticize members of the armed forces as “lazy, useless and cowardly”? Or the Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs refer to farmers as “idle, corrupt and inefficient”? Well, of course, to the best of my memory, neither of these things has ever happened. It seems to be an accepted convention that the relevant government ministers for the military and for farming are broadly supportive of the people working in these jobs. They even tend to actively promote and support their interests.

Yet the same clearly does not apply with all types of employees and their relevant ministers. I’m thinking in particular here of social workers and teachers.

Social Workers

It’s been well known for some time that people working in social services get a bad press. A notorious example was the tragic case of “Baby P”. This led to the hounding by the press of the head of Hackney Social Services. The tabloids effectively bullied Ed Balls, minister at the time, into leaning on the local authority to sack her. She, rightly, went on to win her employment tribunal case for unfair dismissal. It’s obvious that social services departments have been understaffed for years: I remember attending a talk given by the chief executive of a former local authority lamenting his 48% vacancy rate in permanent posts.

Overworked social workers daily have to make heart-rending decisions such as whether to keep a dysfunctional family together. Often they are “damned if they do” and “damned if they don’t”. It makes you wonder why anyone would choose social work as a career. Unremitting criticism, including from the responsible government minister, is bound to be counter-productive in the longer term.

Teachers

A similar trend is apparent in our schools. A government report issued in August forecast a shortage of teachers as a result of too few people taking up training. A record number of teachers are leaving the profession. It’s not hard to see why.

Over the past couple of decades, the teaching profession increasingly used evidence-based research to improve teaching practice. They gradually learnt what worked and, as a result, standards improved. The great British public – or at least the media – would have none of this. When exam results fell year on year, as they did occasionally, the press screamed at teachers’ failures to do their jobs. More often, results rose year on year. And the result? The press complained that exam standards were falling – the tests were getting easier. Another example of “damned if they do, damned if they don’t”.

At least during the New Labour years, Education Secretaries gave praise where it was due, whilst continually demanding ways to improve teaching and learning. And yes, teachers complained at the excessive pace of top-down reforms and the amount of testing.

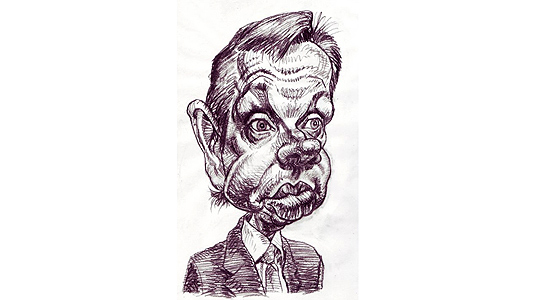

Things changed dramatically after the 2010 election. Murdoch journalist and new-kid-on-the education-block, Michael Gove, declared war on teachers. “The blob” was his favoured term of abuse. Reforming zeal took on a whole new dervish-like form. Policy changes became based not on the evidence of what works, but on ministerial whim. Websites, blogs and social media were dedicated to the teaching profession swapping tales of Gove’s latest stupid pronouncement. Most of the profession was laughing at him behind his back as means of coping. The Department for Education and Ofsted vied with each other to heap the most criticism on the reviled teachers. Staff working as school inspectors for outsourced private companies would often swoop like an invading army on schools who failed to adopt the new ideas. The aim was to force reform against the wishes of parents, governors and teachers.

In my role as a school governor, I attended a meeting last month with a number of head teachers which was basically to make contingency planning for a feared possible Whitehall swoop. Our aim was damage limitation. At the end of a nearly two-hour discussion, we turned and looked at each other. We sadly lamented that none of the time we had spent in that meeting was in any way focussed on the children’s needs or on improving their education. Such a waste of time and energy! This pattern gets repeated all over the country. And mightily disheartening it is too!

Gove’s successor, Nicky Morgan, has toned down the rhetoric, but much of the madness and dogma continues.

So what is it about the military (including arms manufacturers) and the farmers which leads Government ministers to act as their cheerleaders – but for teachers and social workers it’s a constant barrage of criticism?

Write your answers on one side of the paper only, please.