The City of London claims to be the biggest and most important financial centre in the world. In strictly numerical terms, I’m sure it’s true. According to Wikipedia, it is “the largest financial exporter in the world which makes a significant contribution to the UK’s balance of payments”.

Finance Sector “Facts”

Financial services account for nearly 10% of GDP (national income) and employ nearly 4% of its workforce. Business services and finance combined have risen from 5% of GDP in 1948 to 32% in 2013. Gross Value Added (GVA) is a net figure of the output of a sector less costs of goods and services consumed. On this basis, finance’s GVA is 8% of the economy as a whole. Half of this amount comes from London. The City employs 415,000 people (2014 figure), up 25% on 2009. Financial services paid – or collected, e.g. income tax – 11% of the government’s tax receipts.

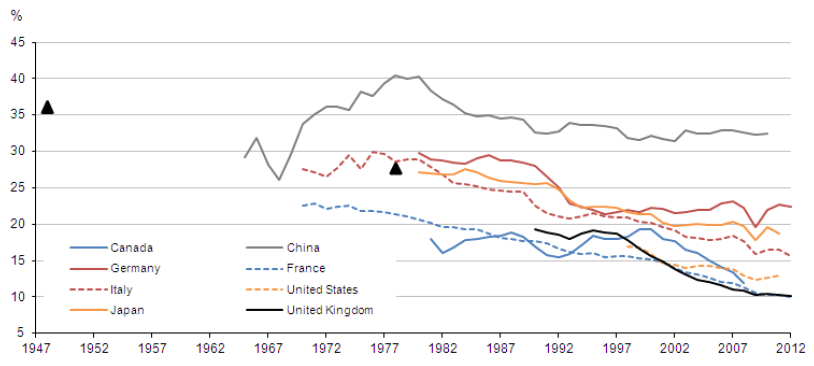

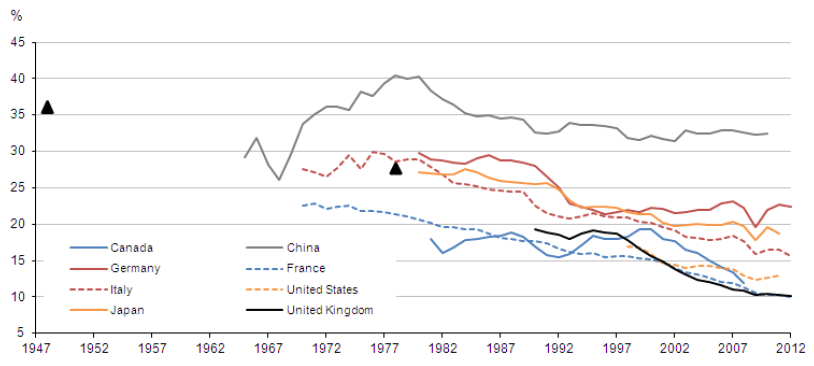

The flip side of this is the decline in manufacturing since World War II. Britain’s manufacturing sector has declined more rapidly than elsewhere – see graph below. The contrast with Germany is particularly striking.

GVA attributable to manufacturing

(The black triangles above represent spot figures for the UK for 1947 and 1977)

(The black triangles above represent spot figures for the UK for 1947 and 1977)

The City: A Source of Economic Instability?

My earlier blog post Two Gamblers and a Pint of Lager discussed how City trading has grown out of all proportion to the “real” economy. In his brilliantly illuminating 2010 book 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang explains how things have evolved. Here’s a key part of the picture:

- Mortgages are repackaged and resold as Mortgage Based Securities.

- MBSs get repackaged into Collateralized Debt Obligations.

- CDOs get repackaged into a kind of CDO-squared.

- And so on.

As Ha-Joon says, “the same underlying assets (i.e. houses) were re-used again and again to “derive” new assets. A massive tower of financial assets teeter on a tiny foundation of real assets. Financier Warren Buffet calls them “weapons of financial mass destruction”. What we have is potential instability on a massive scale. One small disturbance and the whole pile falls over. And, of course, no one really understands what they’re doing: it’s all a matter of faith.

In an interview following the decision to set up the Women’s Equality Party, Sandi Toksvig spoke of the crisis which brought about the near-total collapse of the banking system in Iceland. Only one Icelandic bank survived. It was set up by two women. One of their policies was to only invest in things they understood.

The City: Centre of a Web of Tax Havens

Much has been written about the tax avoidance activity of multinational corporations and super-rich individuals: the list is endless. Such activity is made possible by a web of tax havens around the world. Places like Jersey and the British Virgin Islands are part of a number of offshore territories linked to the UK. We have more such tax havens than the rest of the world combined. A 2011 article in the New Statesman describes how the City of London Corporation sits at the centre of this web. It is a local authority, but like no other in Britain. It is exempt from many of the laws applicable to the rest of the UK. Businesses can vote in local elections – the number of votes they have in proportion to the business size. The Corporation has its own representative in Parliament and acts as a cheerleader for the finance industry. It’s the last surviving “rotten borough”.

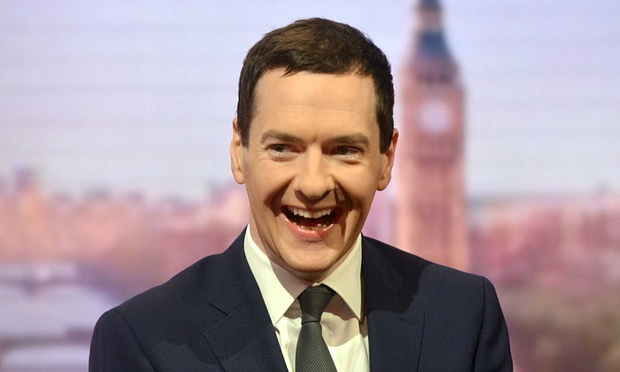

With over 50% of donations to the Tory Party coming from financial institutions in the City, it’s easy to see why this government really means “the interests of the City” when it talks of “the national interest”. Whether through ignorance or isolation from the “real” world, Cameron, Osborne and company conflate the two. The British Government lobbied hard against an EU proposal to introduce a “Tobin Tax” in 2011 because it said it would damage the City. It made an unsuccessful legal challenge in 2014 to the European Court of Justice. The UK failed in its attempt to ban plans by 11 EU countries to introduce such a tax in their own countries. The Tax is designed to reduce instability (euphemistically called “volatility”) and to cut the finance sector down to size. It works by introducing a tiny (typically 0.1%) tax levy on all financial transactions. As we have seen, given the huge volume of such transactions each day, the tax would potentially raise billions of euros (or pounds).

Large Financial Sectors Damage Economic Growth

A detailed study by Stephen Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi of the Bank for International Settlements in February this year showed how too big a finance sector damages economic growth. (Their full, rather technical, report can be found here.)

An earlier (2012) paper showed that once finance grows to a certain size*, which in Britain it has, any further growth in the finance sector depresses economic growth. The trend for the past decade is for finance to grow at 5% p.a. So any further growth in the UK’s finance sector will be bad for the economy.

The 2015 paper shows two ways how the finance sector growth suppresses growth in the real economy. The first is a simple “crowding out” argument: finance “steals” from other sectors the best brains coming out of universities. The second is more subtle. The report shows that those countries with large finance sectors invest proportionately more in real estate, creating property “bubbles”. The sectors which suffer most are the R&D intensive industries. The scope for productivity growth in property is small; in R&D-rich industries it is large. As productivity growth is the main long-term driver of increased prosperity, economic growth is depressed.

The performance of the UK economy since 2010 fits this negative pattern exactly. Only two sectors of the economy have prospered. Bankers and financial service workers continue to pocket the proceedings of the government bailouts (“quantitative easing”) and pay themselves bonuses as if the 2008 crash hadn’t happened. And the housing bubble is inflating to the point where more and more younger people cannot afford to get on the housing ladder. Productivity growth has been non-existent. A highly visible example is the trend away from automatic to manual car wash services.

*finance employs more than 4% of the workforce or private debt is over 100% of GDP

The Inequality Engine

My earlier post Chain of Fools explained how most of the innovative “products” introduced by finance over the last thirty years have a common characteristic. They provide a way of enriching the traders in finance at least risk to themselves. They transfer wealth from the majority of the population to those rich enough to have spare cash to invest and to employ the services of financial advisers. A good example is quoted in Thomas Picketty’s 2014 book Capital in the 21st Century. Harvard University spends $100 million a year on financial advice, far more than any other university. It gets a 12% return on its investments – three times the US average for university endowment funds. Once you’re rich enough, you can’t help but get richer.

The upshot is that financial services provide, in fact, a very powerful engine driving up inequality. Any attempts by national governments at redistributive policies such as progressive taxes are like walking up a down escalator.

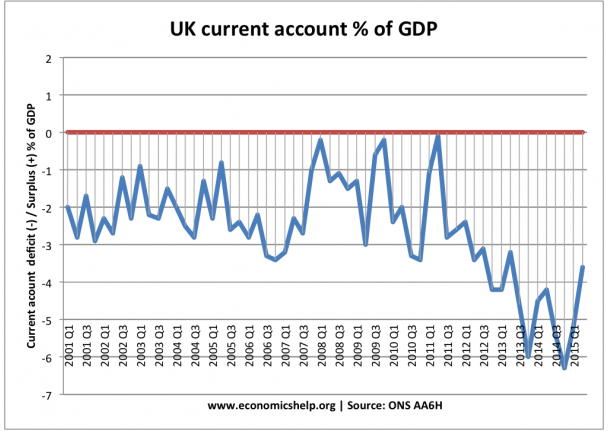

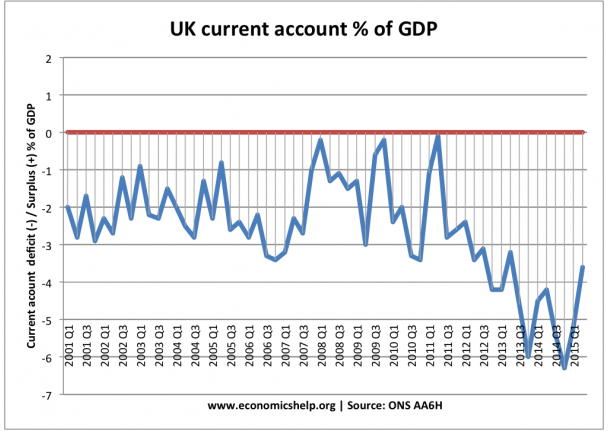

Balance of Payments and Exports

The UK’s balance of payments has been in deficit for the past 15 years, although it can be seen below that matters have been going further downhill since 2010.

The 2014 deficit in goods of £124bn was offset by a surplus of £89bn in services. Finance services supplied a useful £39bn of this surplus. This is perhaps not surprising as the UK economy is responsible for 37% of global financial transactions (with 1% of global population).

The 2014 deficit in goods of £124bn was offset by a surplus of £89bn in services. Finance services supplied a useful £39bn of this surplus. This is perhaps not surprising as the UK economy is responsible for 37% of global financial transactions (with 1% of global population).

However, in value terms, financial services are a poor way to export. Goods, despite manufacturing representing only 10% of our economy, produce 19% of our exports. Financial services, also around 10% of GDP, contribute only 4% of exports.

The underlying picture is that we consume far more than we produce. This has been propped up by overseas investors continuing to invest in the UK economy. The “crowding out / poor productivity” effect of finance over manufacturing described above means this position is not sustainable for ever.

Other Perspectives on the Finance Sector

Finally, I will summarize the work of two independent-minded professionals, the first legal and the second a former key player in finance itself.

Critical Legal Thinking

A 2012 report by the above organisation forensically dissects the value of the various ways banks and financial intermediaries make their money.

30% comes from fees, which the report concludes are extortionate: their words “protection racketeering, fraud, and spivvery” to be precise. 10% comes from speculative dealing with clients’ money, often against their interests. The report mentions that Goldman Sachs traders use the affectionate term “muppets” to describe their clients of these services. 30% is called “other operating income”, an obscure basket of activity believed to include help to clients to hide their money in offshore tax havens. The final 40% comes essentially from charging higher interest to creditors than the banks need to pay themselves. Banks “earn” this by making themselves the only route for clients to capital – as the report says, by “simply being banks”.

Howard Davies article

Howard Davies, former chairman of Britain’s Financial Services Authority, deputy governor of the Bank of England, and director of the London School of Economics, is a professor at Sciences Po in Paris. So he is someone in the know. His Guardian article from 2014 is entitled “Does London’s financial centre boost or harm the UK economy? “

He cites a number of sources, including the 2012 BIS report mentioned above. He makes a few caustic remarks: the expected continuing growth of the finance sector should be good for some other parts of the economy. He cites “Porsche dealers and strip clubs” as examples. His overall conclusions appear to be twofold. Firstly, the net benefit of the finance sector is overstated. And net benefit to the economy as a whole is “mixed”. It’s hardly a ringing endorsement from a man who was at the top of finance tree for so long.

Overall Conclusion

And so to my overall conclusions to the original question: the City, paragon or parasite?

Well, it’s clear that financial services and the City of London in particular are a very important part of our economy and employ a large number of (generally well-paid) people. Any major policy changes which had the effect of destroying large swathes of the sector overnight would be damaging in the short term. Although, of course, finance had a very good try at doing just this in the 2007-2008 crash and the bailout by the government was the lesser of two evils. The finance sector does bring in a surplus on our overseas trade – hardly surprising as the sector is proportionately 37 times larger in Britain than for the world economy. This surplus helps to offset our massive trade deficit in manufactured goods.

But look at the other side of the “balance sheet”. Finance is a major source of economic instability, as the 2007-8 crash showed. It facilitates tax avoidance through its network of tax havens. Its growth is damaging to productivity and long-term growth in the economy as a whole. And it repeatedly creates property bubbles instead of investing in productivity-enhancing industries. Finally, it powerfully drives up inequality.

So, overall, that makes it more parasite than paragon. It’s high time we started rebalancing our lop-sided economy before the next crash.

(Sources for this post include: City of London Corporation, Office for National Statistics, House of Commons Library, Bank of International Settlements, The Economist, The Guardian, New Statesman)

I was interested to note that Citizens Advice has commissioned this Team to produce a report, published last week, called Applying Behavioural Insights to Regulated Markets. I was keen to read their analysis and recommendations. It covers much the same ground as my blog post Cat and Mouse published last September. The new report is wider in scope than my post, covering energy (gas and electricity), telecoms, personal finance and pensions.

I was interested to note that Citizens Advice has commissioned this Team to produce a report, published last week, called Applying Behavioural Insights to Regulated Markets. I was keen to read their analysis and recommendations. It covers much the same ground as my blog post Cat and Mouse published last September. The new report is wider in scope than my post, covering energy (gas and electricity), telecoms, personal finance and pensions.