7th May 2019

With just one year to go before the 2020 General Election, Guardian journalists review the achievements of the Government in the last four years.

Economy

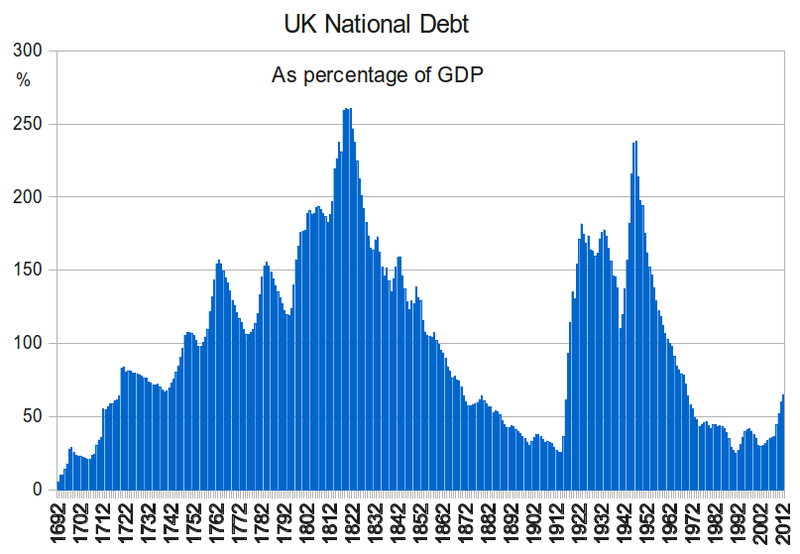

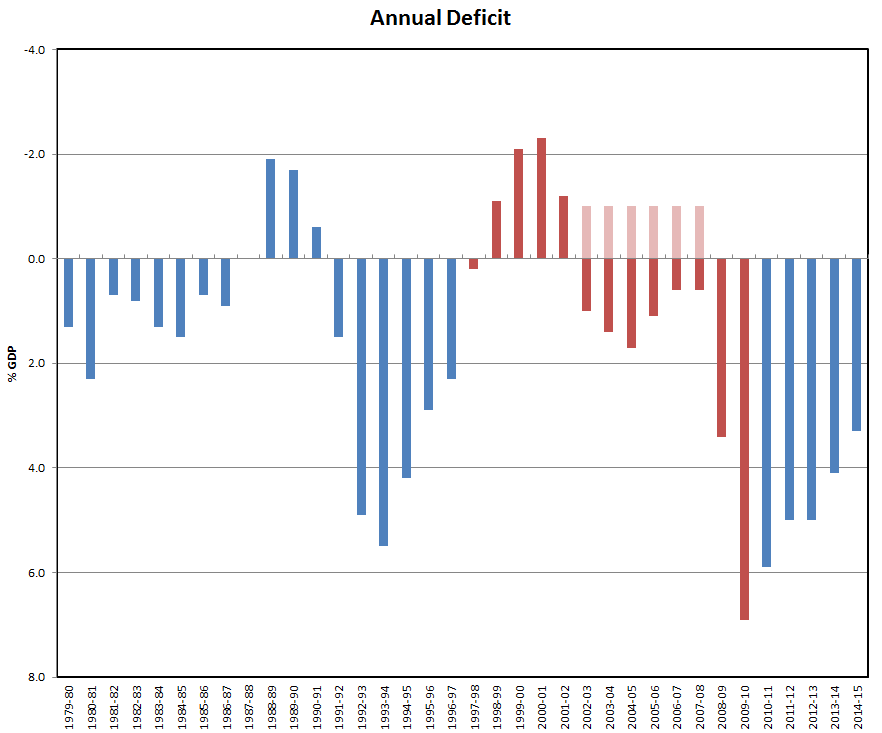

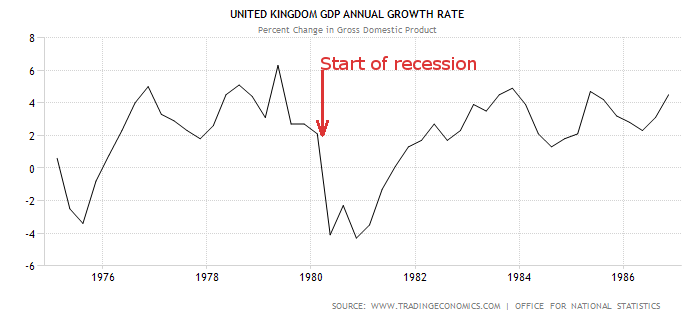

Following phase two of austerity measures introduced after the 2015 general election, the UK economy returned to recession in Q4 2015. In a rare show of consensus, economists agreed that the Chancellor had simply repeated the same mistakes from five years earlier.

Thanks to effective news management from Tory-supporting newspapers, public opinion swiftly blamed the new economic crisis on a combination of the EU, immigrants, the poor and the mess left by Labour in 2010.

Europe

David Cameron began well at the start of the promised renegotiations of the UK’s relationship with the EU, by promising to “look after Britain’s interests” whilst “keeping the UK at the heart of Europe”. However, his negotiating style quickly returned to form: lecturing to all foreigners and getting very red in the face when they disagreed with him. His potentially closest allies in Europe quickly lost patience and any sympathy for the UK’s position. This led to a complete breakdown in negotiations. This forced Cameron to throw his full weight behind the “out” campaign in the late 2016 referendum.

Scottish Devolution

A similar negotiating style on devolution terms for Scotland led to the Scots unilaterally deciding to hold a second referendum on leaving the UK: this time, the vote was 63% “yes”. Cameron initially refused to recognise the vote as legitimate, but, as a result of the small Conservative majority, the threat of a revolt from ten of his “glad to see the back of them” backbench MPs forced him to accede to the Scots’ demands.

On 1st January 2018, the UK left the EU and Scotland left the UK on 24th June the same year. Nicola Sturgeon had successfully negotiated an interim arrangement whereby Scotland kept all the rights and obligations of EU membership between these two dates.

Northern Powerhouse

Initially, the renewed offer by the Chancellor of devolved powers for northern cities was met with a warm reception. When an observant northern city councillor revealed that the “small print” in the deal meant that the “powerhouse” proposal was no more than a smokescreen for further cuts in Whitehall funding for local government, the atmosphere quickly soured.

A Treasury spokesperson attempted to justify the cuts using the argument that the entrepreneurial spirit “set free” by the proposals would mean northern cities would need less “subsidy” from the south. Critics soon compared this assertion with the argument used for the, now twice failed, claims in 2010 and 2015 that cuts to public spending would help get the economy moving.

A small group of Labour councillors in Manchester led a campaign “the Tories don’t care about us up north” which quickly took hold of public opinion there. Demonstrations, followed by rioting akin to that seen in the Thatcher years over the Scottish poll tax “experiment”, soon got out of hand. In the aftermath of the riots, the “offer” of devolved government was withdrawn by Westminster.

Boundary Changes

Negotiations between Holyrood and Westminster proved tough for Cameron, particularly after the northern riots. Eventually, he was forced to concede that the former border between England and Scotland be moved roughly 250 miles south, with some detailed boundary issues still to be settled at the time of writing.

Two significant enclaves were agreed, one north and one south of the new border, to allow for exceptional cases.

In the north, Cheshire opted to remain in the former England, and a short stretch of the M6 was appropriated as a “safe passage” for residents of Cheshire to travel “without hindrance” to the southern mainland.

In the south, following a remarkable campaign by a group of leading academics, hi-tech business leaders worried about loss of EU markets, students and party activists, Cambridge staged its own referendum in which they overwhelmingly voted to join Scotland. A section of the A1 and A14 was similarly reserved for Cambridge residents to travel freely north. As a precaution, the security barrier on the A1 was built to a greater height and with additional security features at the Grantham bypass.

The tabloids quickly dubbed the security fence the “Farage Barrage” and the Cheshire enclave “Dacre’s Acres”. The latter was in honour of the leader of the most consistent misinformation campaign for the Tories and as a topical reference to the reintroduction, in the south, of capital punishment – for anyone found using metric measurements.

Welcoming Cambridge and northern England to the Holyrood parliament, Sturgeon stated that Scotland would be the heart, Cambridge the brains and northern England really would be the manufacturing powerhouse of the newly independent country.

The New Free State

Three months before the start of border controls between the new “Caledonia” and “Cameronia”, residents of Lincolnshire objected to the inconvenience of having the A1 as a barrier to the shortest routes to other parts of England. An informal local plebiscite led to Lincolnshire opting to join the new Free State of Greater Clacton and thereby opting out of both their new neighbours.

Welfare Reform

In his first move following partition, Ian Duncan Smith successfully negotiated an exception to the total closure of borders between Greater Clacton and the rest of the world. This was to sub-contract all the work of Job Centre Plus offices – now re-branded Work Makes Free – to new processing centres in Lincolnshire. To overcome the problems of very poor transport links in the area, all roads were designated one-way only (inbound). Benefit claimants will now need to make their way as best they can to the new centres.

Trade and Immigration

Cameronia’s record – and rising – trade deficit was reduced temporarily by the loss of two key ports: Felixtowe, now permanently closed, and Liverpool, now in Caledonia. Work started to revive the fortunes of the port of Bristol. This was helped by the small-scale reintroduction of the slave trade, otherwise known as “tier 2 immigrants” in the new two-tier immigration points system. Tier 1 immigrants, who are allowed unrestricted rights to enter and leave Cameronia, are now defined as those with an annual income of at least £1.5 million, or capital of £100 million.

In Other News…

Sport

- The national boundary change forced Aston Villa Football Club to relocate to West Ham at the start of the 2018-19 season.

Transport

- Chaos on the A14 as academics from other Universities in the south try to reach Cambridge before the border closes.

- TfL re-brands the Oyster Card: now called the Shark Card. All card purchasers must show proof of income of at least £150,000p.a. The poor must use the (reduced) bus services only. With the London Congestion Charge abolished for company cars, bus journeys are slower. Health experts have expressed fears of a serious health crisis, with poor workers in London now averaging less than 3hrs sleep a night, in order to get to work on time.

- In an unusual case of nominative determinism, the operators of the newly-opened Crossrail service state that all users must carry a copy of the Daily Mail or Daily Telegraph when travelling. Commuters are required to look up from their newspapers at frequent intervals and make disapproving tutting sounds to show how cross they are – about benefit scroungers, poor people, single mothers, etc.

- Osborne announces that completion of the HS2 rail link is to be brought forward and the route modified, with the northern terminus at Tatton.

- Richard Branson said he was “shocked” to discover that Virgin Trains is the surprise winner of the Islamic State Railways contract.

Law / Open Government

- The Freedom of Information Act is replaced by a Freedom of Misinformation Act, dubbed the “Right to Lie”. This grants government ministers and newspapers (except those not owned by tax-avoiding multimillionaires) full legal indemnity when stating any untruths . Ministers quietly slipped in a clause allowing the Prince of Wales to place black spiders on opposition benches in the House of Commons, to disrupt speeches.

Europe

- A group of leading academics and economists presented a controversial report to the European Parliament about the effects of deregulation of financial services since the 1980s. The report concluded that all new financial products and services introduced since then were essentially giant Ponzi schemes designed to transfer wealth from middle- and low-income households to the super-rich and were of negative social value. The EU parliament voted by a 2 to 1 majority to ban these new practices within the EU within a 3-year period. After fierce negotiations, the EU Council of Ministers reluctantly agreed parliament’s recommendations.

Financial Services Regulation

- Cameron steadfastly refused to make any changes to City practices following EU pressure. As a result of this refusal and Cameronia’s opting out of European Human Rights regulations, EU trade sanctions were imposed from 1st January 2019. Estimated job losses from these sanctions and the relocation of many multinationals following Brexit vary between 2 and 5 million.

- A reluctant President Clinton eventually agrees to reform Wall Street slowly – arguing to her domestic objectors that the USA’s much broader economic base than former UK means that Americans will benefit in the longer term.

Employment

- Following the abolition of all employment laws, companies increasingly introduce “registration fees” – typically £50 to £75 a week – for workers to retain the privilege of zero hours contracts. This, in turn, sparks a rapid increase in “no gain no pain” lawyers typically charging non-refundable fees of £250 to workers disadvantaged by the changes.

Families

- Social workers report that sexual abuse within families has risen 25% following the limitation of housing benefit to one bedroom only, regardless of family size.

Religion

- The Archbishop of Canterbury announced the discovery of a rare early scroll casting new light on the scriptures. The archbishop stated that one of Jesus’ most famous sayings was misquoted and should now read: “the poor shall inhabit the earth” (see also Lincolnshire above).

Consumer

- In an unusual example of government interference in the workings of the free market, a Customer Loyalty Penalty act was introduced, to demonstrate that competition is always the best way to protect consumer interests. The Act decrees that all utility and insurance companies must impose a minimum 10% plus inflation price increase for any consumer too lazy to switch providers on renewal. Experts say this will make very little difference, as it merely formalizes current practice.

Politics

- George Osborne finally announces what many had suspected: that his part-time job as Chancellor of the Exchequer is too disruptive of his main role as chief political strategist for the Tory party. The job will be devolved to the “big four” accountancy firms Deloitte, PwC, Ernst and Young and KPMG. Contracts will be awarded and managed by newly-created Criminal Commissioning Groups run by convicted fraudsters.

- MPs have voted to award themselves an annual pay rise of 25% for each year of this parliament. Ministers state that money will be saved overall by the introduction of a disloyalty penalty. An MP’s salary will be permanently reduced by 10% each time he or she votes against the government. A threatened last-minute revolt by the few remaining Tory “awkward squad” backbenchers was headed off by the creation of an appeal panel to consider exceptions to the penalty rule. The panel members will be George Osborne, Michael Gove and Chris Grayling.

- In an attempt to distract from the breakup of the United Kingdom, the Conservative Party has formally renamed itself the “Conservative United New Tories”.

Benefits

- A new kitchen tax will be applied to all private dwellings with more than one kitchen. Tory party donors, government ministers and royal family members are exempt.

Health

- The new Mental Health Act defines proponents of Health & Safety rules as having “gone mad”.

English Language

- A small group of Oxford academics who chose not to move to Cambridge have been commissioned by the government to produce a New Oxford Dictionary: the Rightspeak Dictionary.

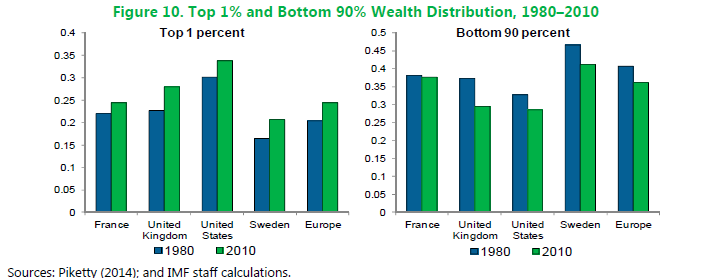

In the UK, the top 1% own almost as much wealth as the bottom 90% of the population. Only the USA has greater inequality and the gap between the blue (1980) and green (2010) bars is biggest for the UK. Sweden, by comparison, although getting worse, shows that it doesn’t have to be this unequal.

In the UK, the top 1% own almost as much wealth as the bottom 90% of the population. Only the USA has greater inequality and the gap between the blue (1980) and green (2010) bars is biggest for the UK. Sweden, by comparison, although getting worse, shows that it doesn’t have to be this unequal.