… with the Oxbridge Blues again

One of the enduring myths in Britain is that grammar schools aided social mobility. I will aim to demonstrate this really is a myth.

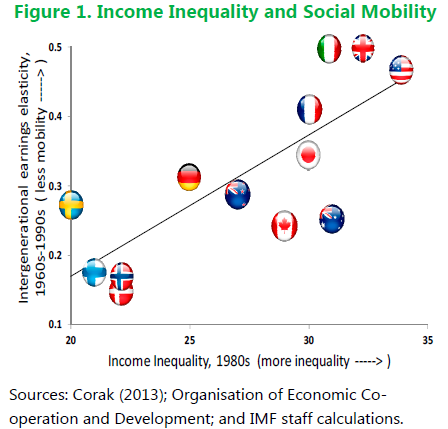

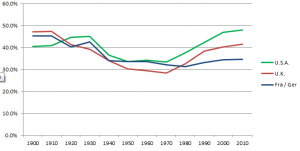

It’s undeniable that the UK has the worst record on social mobility in the western world: the graph below, taken from a just-published IMF report, shows the UK (alongside Italy) firmly at the top of the graph – which means we’re the (equal) least socially mobile country in the developed world.

So where does the myth come from? Ofsted disagrees, so it’s not them. One source is Conservative Voice, the Telegraph quoted Boris Johnson as saying so and Nigel Farage in the Express reminds us it was all Margaret Thatcher’s fault! But then, some commentators in the Telegraph disagree with others…

It’s generally agreed that social mobility was greater in the 1950s and 1960s than today and there were more grammar schools around then. But that coincidence proves nothing.

Changes in the Economy

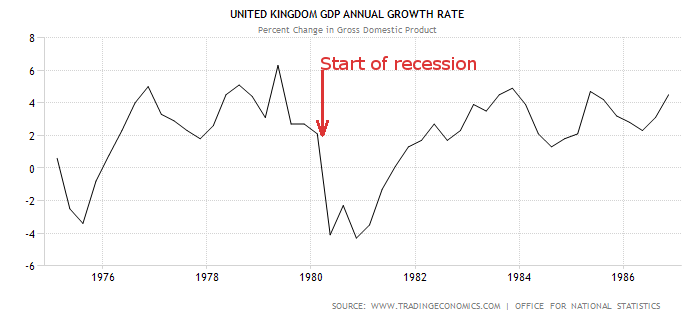

During the 1950s and 60s, there was a major shift in working patterns, as increasing disposable income and technological progress shifted the balance of employment away from traditional working class jobs to a higher proportion of white-collar workers. Growth averaged 2.8% a year. This shift in the economy created the demand for more middle-class workers, which necessarily meant that many people from a working-class background moved up the social ladder.

By contrast, between 1980 and 2014, when growth was lower at 2.1% and most of that was grabbed by top earners as inequality increased, technology tended to destroy the middle-class jobs that were created a few decades earlier. More recently, the shift away from reliable, well-paid jobs to part-time and zero hours contracts has witnessed a halt to long-term rising productivity and standards of living. Who would have imagined forty years ago that carwash machines would be replaced by manual labour in the 21st century?

So, for social mobility, “it’s the economy, stupid” that did it – not the education system.

Other Countries

Another look at the graph above shows that, as to be expected, social mobility in the Scandinavian countries, clustered around the bottom-left of the graph, have very much higher rates of social mobility. But all these countries have some sort of comprehensive education system. So, their schools are not holding them back. It’s also striking how low inequality goes with high social mobility. This is fairly obvious if you think of mobility as a ladder. It’s much easier to climb if the ladder isn’t so long and the spaces between the rungs are closer together.

So let’s kill off the “return to grammar schools” myth once and for all.

Myth Two

And while we’re myth-busting, take a last look at the graph above and notice which country is next-highest on the graph (meaning second worst for social mobility). It’s the United States of America, the most unequal of all the western states. So the Great American Dream that, through hard work, anyone in America can make it to the top is also a myth. As Harvard Professor Michael Sandel said in a 2011 lecture broadcast on BBC4, “The American Dream is alive and well – and living in Denmark”.

So that’s two myths busted for the price of one!